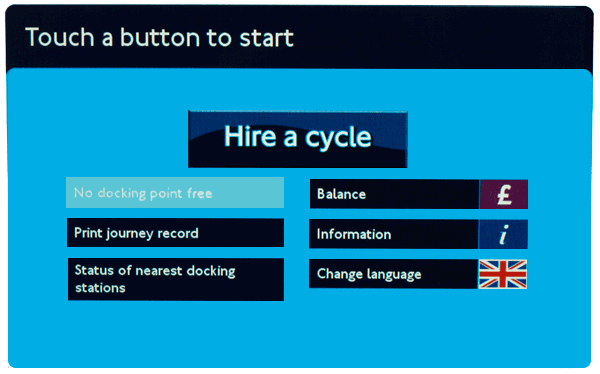

Officially known as Barclays Cycle Hire, Transport for London’s blue hire bikes are a ubiquitous sight around London. Hiring a bike is fairly straightforward using the interactive kiosks located next to docking stations around the city.

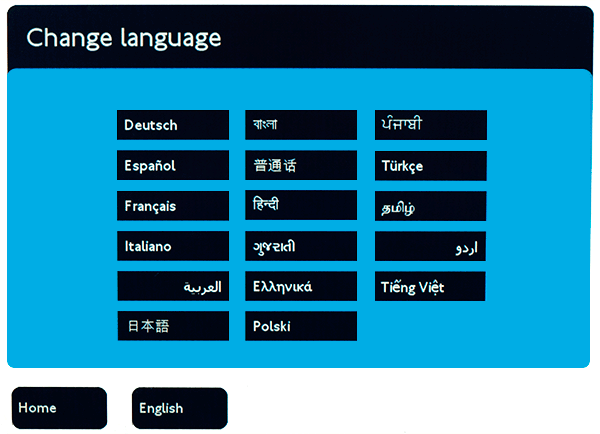

The kiosks support seventeen languages: along with English, the system is localised in German, Spanish, French, Italian, Arabic, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Chinese, Polish, Punjabi, Tamil, Turkish, Urdu, Vietnamese and Japanese.

The icon for language selection is a British flag:

However, this is the only flag used for language, as shown on the language selection screen below:

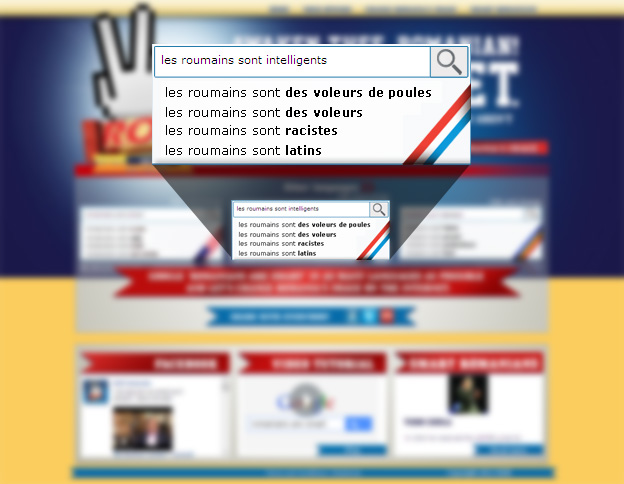

The use of the British flag is an interesting choice. While the system doesn’t explicitly use flags to represent languages, it does use a flag to show availability of languages.

It would be very interesting to see stats on how many users actually find and use localised versions of the kiosk. By using the British flag alone, could the system possibly miscommunicate itself?

London’s official promotional organisation London & Partners provides visitor statistics to London by nationality. The top three nations are the USA, France and Italy. This allows us to begin to understand the types of users who would be using the system.

Currency?

Looking at the top three types of visitors, could users mistake the British flag for a currency icon rather than a language icon? Payment is only available in the Great British Pound — visitors from the US may want to use US dollars or visitors from the EU may want to use the euro. (This may be either cancelled out or confused even further by the pound icon next to ‘balance’ on the home screen in the top right.)

Probably not a major issue — but it does suggest the language selection proposition represented by the British flag is not as strong as it could be.

Exclusivity?

As a visitor or new immigrant, does the British flag suggest it could be exclusively for British citizens only? By virtue of the flag being isolated here, again this is a possibility. Ironically the presence of other flags would probably negate this.

Improvement through prioritisation

Obviously the majority of visitors from United States would not need translated content. Many French, German and Italian users may have a good enough grasp of English to navigate the system without translation — so users from those countries might not use the translations as much as users from perhaps Asia or South America.

The most effective strategy for presenting translation options would be to find the balance between the group of language speakers that would benefit most from translation versus the group of language speakers that comprise the largest number of users.

Once establishing this, language selection can be based on this priority.

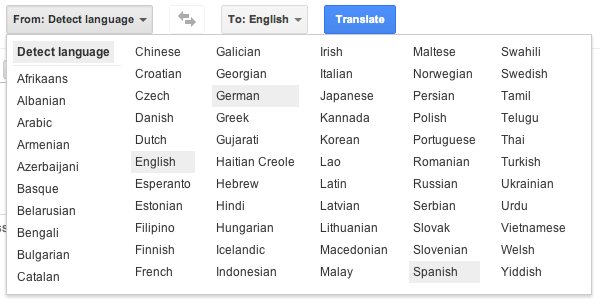

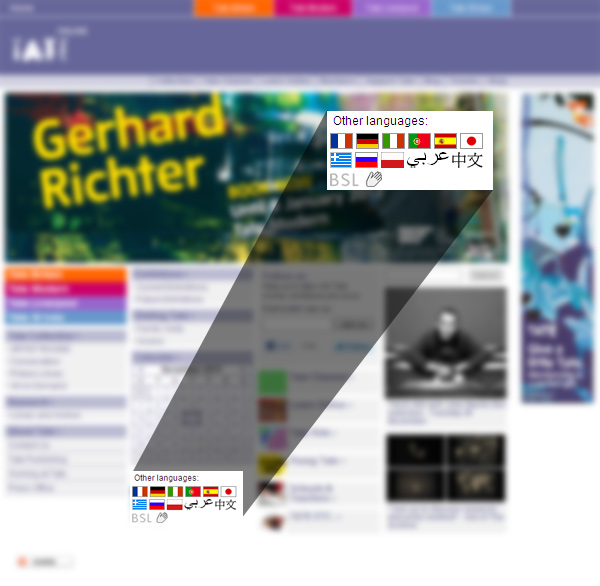

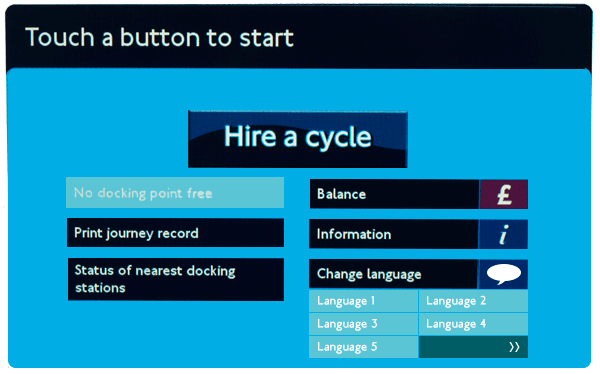

The new design above shows a more generic speech bubble icon instead of a flag to represent language. It also displays five languages on the home screen and a button alluding to further languages being available.

Would the above screen work better at showing language options? Potentially — of course the only true way to know would be to test this with real users.